If you live in America and need to complete some basic errands, say going to the grocery store and barber, chances are that you will get into your car to drive 10 to 20 minutes between each location. This is not some natural optimal solution but a state that we have worked towards often intentionally.

The rapid adoption of personal automobility devices over the last 120 years has caused the growth of suburban centers. The adoption of these suburban centers, which are overly focused on cars, have negatively impacted American society, culture, and its future.

The Ascendance of Automobility

For much of the American history everything was either within a small town that was walkable or accessible by horse and buggy. The advent of the railroads allowed people to access places that were previously inaccessible or unreasonable. Street cars allowed for easy and often cheap way of shuttling people from one neighborhood to another section of a town. However, most people still didn’t have any way of transporting themselves over longer distances. This all changed with the automobile. Suddenly distances of many more miles were achievable for anyone who could afford a car. As Ford started mass producing cars automobile registrations grew incredibly rapidly. In 1912 there were under one million automobiles, that grew to over 27 million privately owned and registered vehicles in just 28 years (1940). Following World War II there were was an exponential growth in car ownership which lead to new issues.

Reshaping the Landscape

The growth in private ownership of cars, fueled the Federal-Aid Highway Act of

1956 which further focused development work on the private automobile, instead

of public transit options like streetcars and buses.

(Interestingly enough the Federal-Aid Highway Act only mentions buses 12 times, almost exclusively in relation to taxation.

The rise of car ownership in cities lead to another issue, where would people park them? To deal with this issue new housing developments were being designed in ways that were overwhelmingly focused on how best to suit the car.

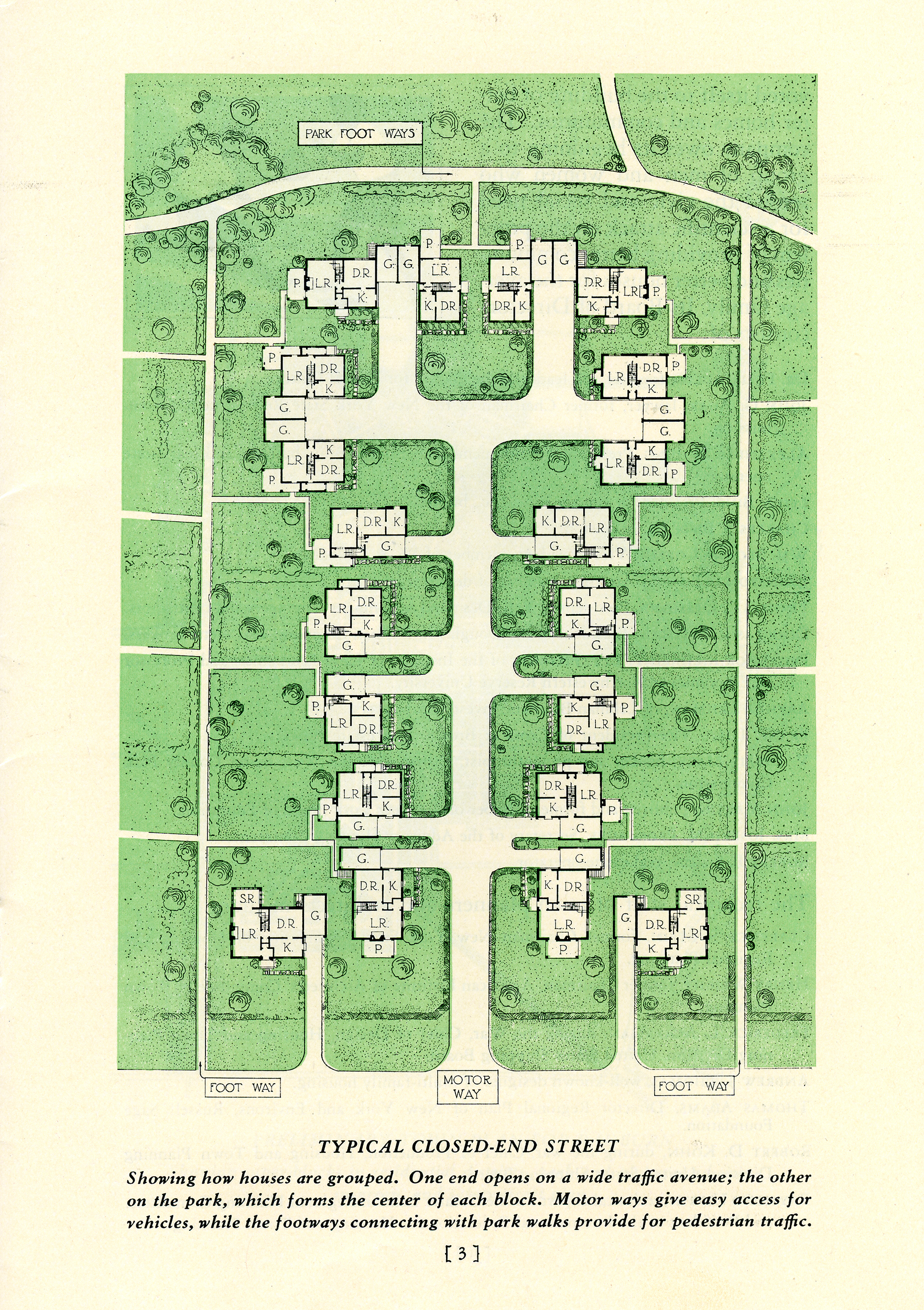

One of the earliest examples of how cities started planning for cars is Radburn,

New Jersey.

Ironically enough Radburn shows an alternative model for how the suburb could have been planned for both cars and houses. Radburn had the roads and drive ways entering the back of the houses compared to the now standard front orientation.

The model from Radburn also set the standard for the elimination of sidewalks to make roads as wide as possible, which allowed for more through traffic.

Because these sorts of

developments were focused around the car this further incentivized more

Americans to get cars which then further fed this self fulfilling cycle.

Shopping centers, and schools started dedicating larger portions of their land

just to keep up with the demand of parking.

As more Americans moved to the suburbs public transit systems had trouble keeping up and functioning in an environment that was not designed for those sorts of vehicles. The design philosophy of these housing developments itself gave birth and nurtured the conditions for car dependency. The car enabled sprawl, which sprawl required cars which made an impressive feedback loop.

Urban Sprawl is the process of spreading out of urban developments near a city.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_sprawl

One of the things I love about Portland is that it resisted this kind city redesign as people started moving out from the city center. Neighborhoods that were developed in the years before cars were common still have a unique charm to them.

This isn’t to say that Portland was able to prevent sprawl. We have plenty of it in Happy Valley, Gresham, and Milwaukie. I went to a high school in Milwaukie and getting to anyone’s house in Milwaukie was a real pain by public transit or by bike. I recall once trying to meet with a study group in Happy Valley and it taking me only 30 minutes walk 10 blocks to get dropped off, but over an hour to take the bus to the transit station. This region of the greater Portland area was not designed for people without cars. This is a stark comparison to my daily commute to work during my gap year. I simply walked one block to the bus stop and then took the bus ~80 blocks downtown, all under 20 minutes. Not to mention the countless coffee shops I could walk to from both home and office.

Societal and Cultural Transformations

As America grew to love the car, “car culture” started taking hold. This culture

fit in well with the country’s deep embedding of

automobility. The car was no longer just practical, but a part of your identity

and lifestyle. The car reshaped American’s leisure and consumption.

The car enabled new forms of recreation like road trips and drive-in theatres.

A successful trip was now measured in how many miles you drove, more being much more successful.

The highway itself further enabled long distance travel. New businesses started

popping up that were designed for the car, drive-in businesses and retail parks.

I recently learned that there was a movement from Gresham to try to get an additional interstate installed right through the middle of Portland to connect the city center to Gresham. It would have been a freeway of epic proportions, almost to the scale of some Texas 8 lane freeways.

Luckily freeway was never built, but it left a lot of valuable documents and

history in its wake. One of the documents produced by the later mandatory

reviews was an environmental review.

This trove of analysis is fascinating in how it shows that installing a freeway

right through the middle of a community would knock out tons of single family

residential and educational regions. The report acknowledges that even though

new ways of accessing the center of Portland were built the economic center was

unable to prevent the loss of people moving away from the city center. In

essence, the roads that let people move away, weren’t enough to keep people

coming back to the downtown. The report also acknowledges that it would have

needed to remove 1,400-1,700 homes, displacing between 4,074-4,947 people.

The report even goes on to highlight that (emphasis added by me): “the freeway, which

would diagonally traverse the central Franklin district, could

have a major limiting effect on pedestrian circulation patterns

in the area, and could compound the present disruption of local

land use patterns by high volumes of through traffic.”

Economic Implications

A cost benefit analysis by researchers in Europe of how the downfall of automobility can impact Europe’s economy shows an overall net benefit compared to cars which cost €0.11 per km whereas more sustainable transit like walking and cycling have a net benefit of €0.37 and €0.18 respectively. They specifically call out that cycling is a benefit worth €24 billion per year and walking €66 billion per year.

A separate analysis in the United States showed that the parking of cars alone

was incredibly expensive from a land use perspective. The researchers estimate

that 6% of urban land in 2010 was dedicated to parking lots with an average of

2.2 parking spots per registered vehicle. The study only focused on a small

region of Indiana, roughly 1,302 km^2.

One way of quantifying the impact of using land is by looking at the ecosystems

service value (ESV), which puts a number to the loss of the environment.

The impact of parking in that small county was $58.6 million. Replacing all that

land with wetland yields an ESV of $22.5 million which 38% increase in ESV.

Hope for the future?

Europe managed to avoid reshaping much of their cities to cars because they

didn’t rebuild as much of their cities around cars as America did. Europe also

has been promoting a world beyond automobility for much longer than America has,

leading to a larger adoption already making it a great model for the future.

Paris has already created traffic free zones where cars are not permitted, after

which most residents “haven’t noticed or simply don’t care

about the new measures.”